Introduction

The harmful effects of lead on the human body has been well-chronicled and documented throughout history. Lead is a cumulative toxicant that irreversibly affects multiple body systems and makes its way into the blood, particularly affecting the development of the brain and nervous system as children grow into adolescence and adulthood. Once these high levels of exposure occur in children there is an increased chance of a reduction in IQ, behavioral changes such as reduced attention span, and increased antisocial behavior, among other health effects. There is no safe blood lead concentration for children, but the Center for Disease Control and Prevention has adopted an accepted blood lead level:

In May 2012, the CDC accepted the recommendation from the Advisory Committee on Lead Poisoning Prevention to eliminate the term “level of concern” and to begin using a reference value of 5 micrograms per deciliter based on the 97.5 percentile of the blood lead distribution among U.S. children.

Lead can be found in a variety of places (water, soil, air, gasoline, etc.), but the most endemic source of lead poisoning today remains lead paint present in public and private housing. Older housing structures (those built before 1978) that have lead-based paint continue to deteriorate over time, exposing young children to its harmful effects (mainly in the form of lead dust and paint chips that are ingested). There have been concerns about lead paint for decades. At the start of the 20th Century a Sherwin-Williams publication called white lead “a deadly cumulative poison.” Before that, Benjamin Franklin warned of the effects of lead poison in the human body in a 1786 letter – nearly 200 years before lead-based house paint was banned by the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC).

Now, why is this still an issue for many children and families today if lead’s deleterious effects were reported so long ago? In his book Doubt is their Product: How Industry’s Assault on Science Threatens Your Health, David Michaels argues that though lead was regarded as a highly toxic chemical in the 1900s, it took some time before facts penetrated the minds and actions of government leaders. This delay was due in large part to the persistent messaging of paint production companies and PR agencies touting lead’s safety, a campaign not unlike the misinformation propagated by tobacco companies throughout the 20th century. It wasn’t until there was overwhelming evidence that lead affected industry workers and average Americans (including children) that the CPSC took action in 1978. Since this moment, there has been a significant decline in lead poisoning rates (nationally and statewide) among children through lead remediation efforts, education, and other interventions, but there remains a significant gap in outcomes for those living in low-income, disadvantaged areas.

Philadelphia as a Case Study

Despite the steps taken nationally and locally to curb the effects lead has on children and their families, the chart below illustrates the continued prevalence of negative health outcomes as a result of lead exposure.

In 2004, 12 percent of children tested in Philadelphia had levels of 10 or more micrograms per deciliter of lead in the blood; by 2014, that figure dropped to 1.7 percent. On its face, this looks and sounds like a success, but a closer look shows there are still communities hit hard by the effects of lead.

The national mean doesn't mean anything for a kid who lives in a place where the risks are much higher.

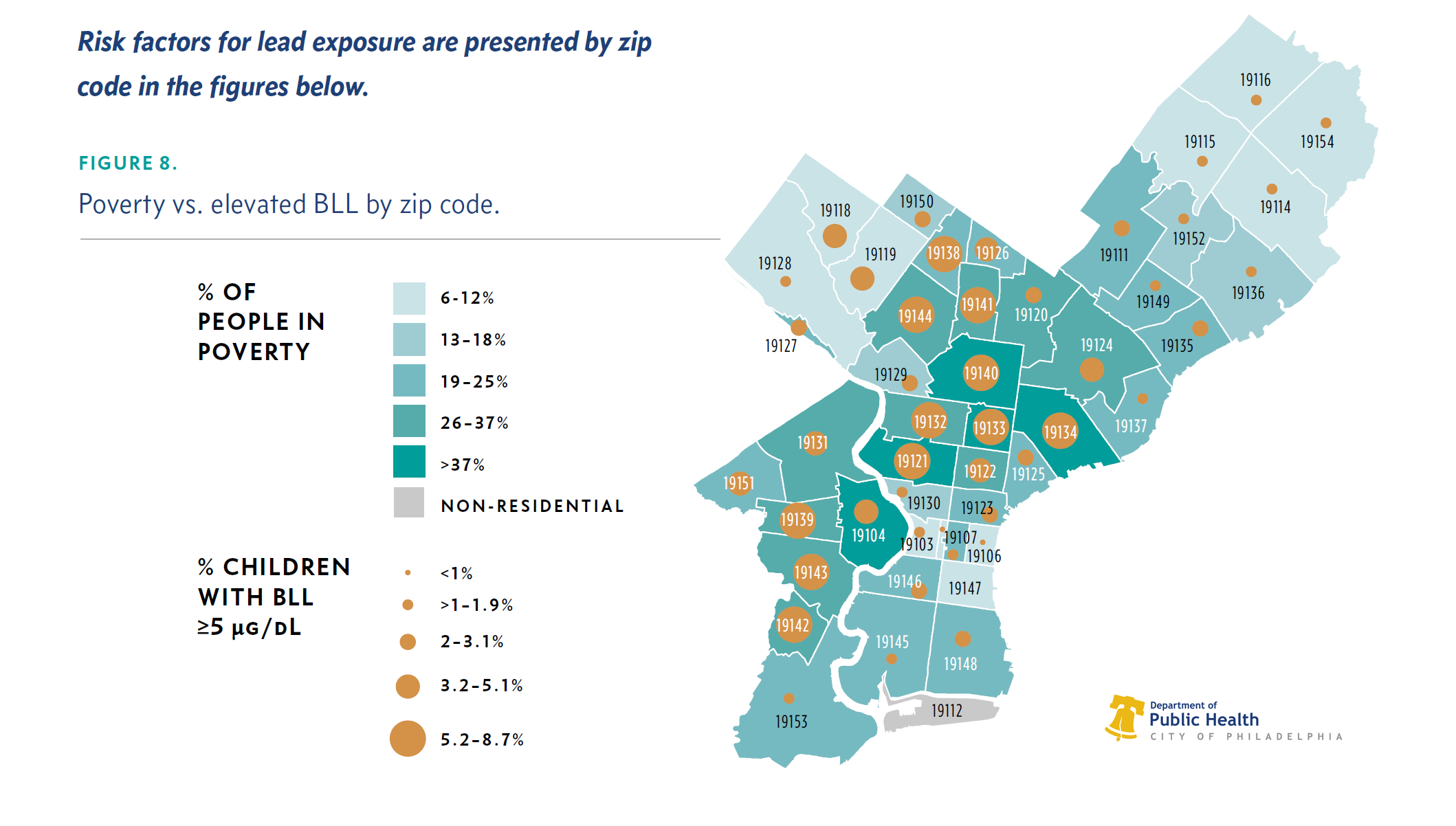

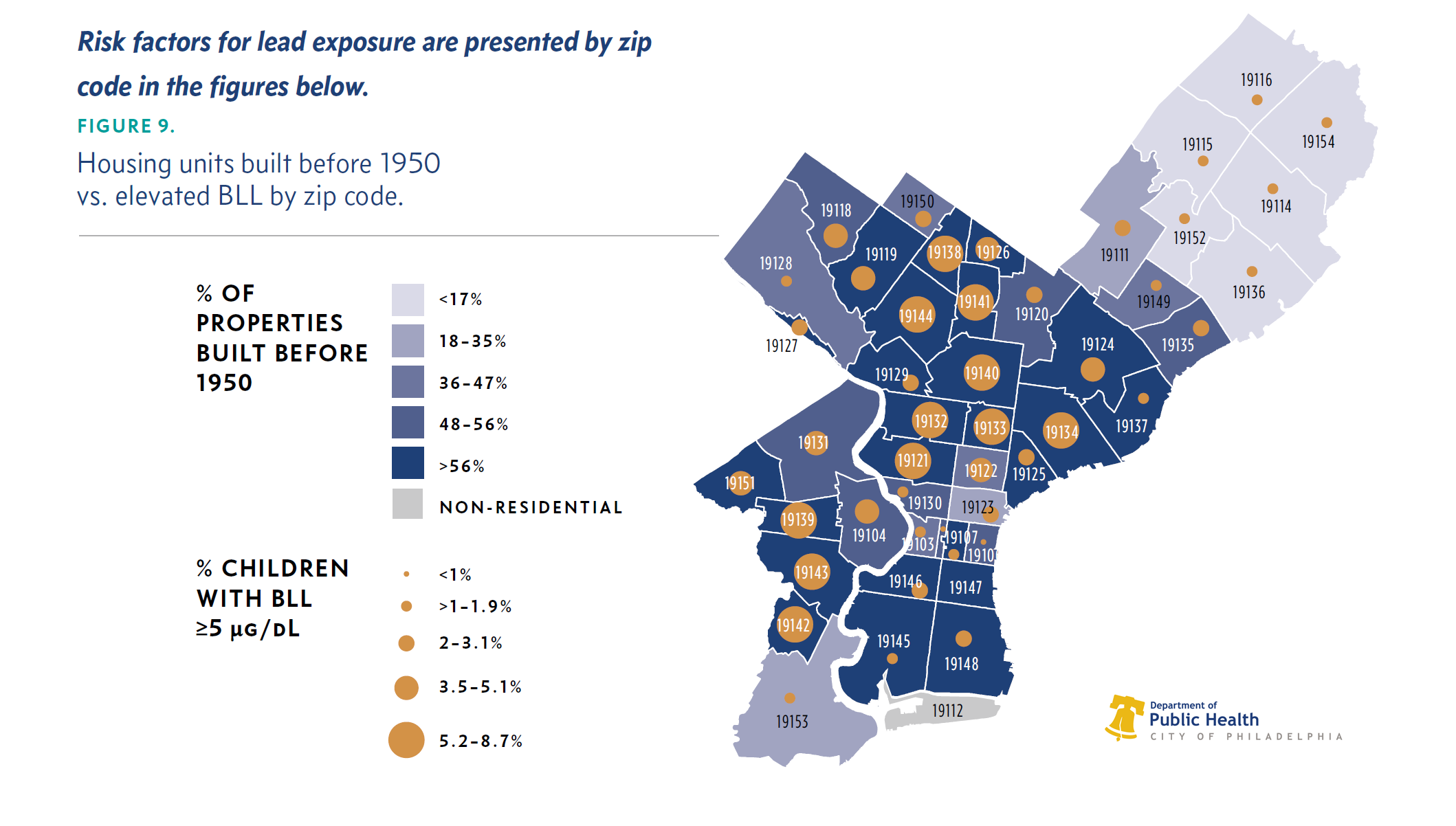

Dr. Helen Egger, chair of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center's Child Study Center CDC describes children who are African-American, living in poverty, enrolled in Medicaid, and living in older housing as having the highest risk for lead exposure. This description is very apt when discussing Philadelphia, as this group, along with Hispanics, face lead exposure at disproportionate rates compared to Caucasians in the city. Approximately 85 to 92 percent of the city’s housing units were built before the 1978 federal ban on lead-based paint. Compared to the rest of the nation (where just over 50 percent of homes were built prior to that year), it becomes easier to see why this issue persists. Couple this with Philadelphia being the poorest big city in the country (with over 25 percent of people living in poverty and residing in deteriorated homes), and the picture becomes just a bit clearer.

The Changing Housing Landscape

In the city of Philadelphia, as in many U.S. cities, rental assistance is provided to low-income families to live in the private rental market through the Housing Choice Voucher Program, which is funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). This public housing decentralization trend is not only privatizing a formerly public system, but may be seen as an attempt to promote freedom of housing and to integrate lower-income and minority families into mainstream society. Voucher programs aim to move many residents of public housing from high-rise public housing structures to the private market, but do not necessarily address the concern that this segment of the population has already been exposed to significant levels of lead and continues to suffer its effects. Moreover, there is no guarantee that voucher-based housing will be lead-free (as we’ll discuss later). Philadelphia has established laws and regulations to limit the effects of lead on vulnerable communities. Below, we’ll discuss why these safeguards have not sufficiently addressed this issue to date, and outline promising practices and models that can create meaningful change.

Laws Currently in Place

There are laws currently in place in the city that have been largely effective in reducing lead poisoning over the years, but there are enforceable laws on the books that are not being enforced, leading to large swaths of children being affected at unacceptable rates. The city’s current lead paint disclosure law mandates that property owners ensure their constructed buildings that pre-date 1978 are certified as lead-safe if they are occupied by a child 6 years old or younger. Despite this mandate, many apartments and homes remain untested. Philadelphia has approximately 5,800 unexpired lead-safe certifications on file, but children 6 and younger reside in an estimated 22,000 rental properties throughout the city. This alone illustrates the shortfall of untested rental units that need to be certified lead-safe, with the enforcement of this law falling well short of its intended goal. There continues to be calls for the city to enforce the laws on the books to hold landlords accountable, but (i.e. having trouble reaching negligent landlords because of concealed identities through LLCs, lack of streamlined proactive process in inspecting high-risk neighborhoods, etc.). Because of this, last year City Council passed two pieces of legislation tied to lead safety that focused on negligent landlords.

Other City Models

Sam Magavern published an article in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, where he took readers on a deep dive of the housing stock in Buffalo and Rochester. These cities have had similar issues with poverty and old, deteriorated housing structures that are riddled with lead-based paint. Many of the solutions proposed in this article are relevant to Philadelphia, and some have already been implemented and have shown results. One that has been echoed by many in Philadelphia is the need for proactive housing inspections. This means not relying solely on complaint-based inspections as a strategy to protect residents of public and private housing from dilapidated, dangerous rental units that can expose children to lead, but adopting universal inspections across the board. Also, it would eliminate the fear that many residents of public housing have of complaining because they don’t want to be evicted for voicing their displeasure and concerns. As mentioned, in Philadelphia there are many who have advocated for this process to be mandated as law.

What would be even better was if we did proactive inspections of rental properties…So L&I [Philadelphia’s Department of Licenses and Inspections] would be going out to rental properties and inspecting for violations and making sure that they know that, when they go to issue that rental license, that that’s a safe house.

Colleen McCauley, Public Citizens for Children and Youth In the past decade, Philadelphia has taken important steps to remediate the lead issue in all levels of housing (including public housing), but there is still much more work to do. For example, Philadelphia Department of Public Health’s Lead and Healthy Homes Program has implemented numerous initiatives to improve the health and safety of housing in the city. Even with this in place, there are still blindspots that need to be addressed as it relates to public housing in the city of Philadelphia. Below you will find some recommendations found on this topic that have been discussed here so far (and some that have not):

Recommendation Corner

Lead-based Paint Abatement: Full removal of lead-based paint regardless of whether or not there is a child 6 years old or younger living at residence. Resulting renovations may be costly upfront, but would be the most effective way to prevent long-term health effects for children. According to the EPA, professional lead-based paint removal would cost about $8 to $15 per square foot or about $9,600 to $30,000 for a 1,200- to 2,000-sq. ft. house. The average removal project costs about $10,000. Also as a frame of reference, in recent years Congress recently directed $170 million in aid to Flint. That's roughly 10 times the CDC's budget for assisting states with lead poisoning.

Universal testing/screening of blood-lead levels for all children: During the writing of this blog post, on June 5, 2019, the Mayor of Philadelphia signed this bill into law that requires providers to test the blood lead levels of the infants they are treating at least twice before the children are 30 months. Pediatricians recommend that children get a blood lead test at around the age of 1 year and again around the age of 2 years. Children who live in older housing or have other risk factors should be screened once a year until the age of six. While The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) requires blood lead testing of all Medicaid enrolled children at 1-2 years of age or at 3 years of age (if not previously tested) this mandate covers all children no matter the insurance coverage.

Lawsuits against paint companies: There has been a movement nationally to bring lawsuits against paint companies that knowingly used and sold toxic lead-based paint before the 1978 ban. A legal fight just ended in California after 18 years, and more legal action in other cities is a proposed method to aid in the high costs of cleaning up lead in the city.

Strengthen registry of licensed landlords: The City of Philadelphia License and Inspections has a property history database that shows the property manager’s permits, licenses, violations and appeals. This registry can be strengthened by taking the necessary steps to increase the number of registered licensed landlords and implementing a section for landlords to prove that their homes are lead-free and safe for occupancy.

Lead Court: A program spearheaded by the Lead and Healthy Homes Program to serve as a vehicle to help renters hold property owners accountable when the housing structure isn’t perceived to be up to code with lead mandates. There have been stories that show this program isn’t as helpful as it should be and needs to be fixed: Read here

Bianca Chun contributed to this post.

LATEST BLOG POSTS

27 June 2024

Did you know that over half of US adults report that either they, or a family member, have experienced a...

14 April 2023

This is the fourth episode of our new Vaccine Confidence series on At the Core of Care. Over the course...

STAY CONNECTED TO NURSE-LED CARE