The current American housing landscape was built over the last century. Understanding its history is essential to address the root causes of the most complex housing problems we face today.

The history of housing policy in the United States includes great achievements that helped millions find affordable housing and improve their dwellings, but it also includes a troubled legacy of racism and inequality that prevented millions more from benefiting from government programs. In many cases, racism and segregation were explicitly enshrined in law, and at other times they were merely accepted practice in implementing the law. We still see the effects of these decades-old decisions today. One of the biggest lessons we can learn from our housing history is that a fair housing policy must both acknowledge and address the history of racism and segregation in housing.

1934 - National Housing Act

The history of public housing in the United States largely begins in the 1930s during the Great Depression with the New Deal programs. Housing insecurity existed before, but the Depression provided the political impetus for the federal government to respond to an issue that had become a crisis. One of the first actions taken to address the nation’s growing housing crisis was the passage of the National Housing Act, which created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) "to encourage improvements in housing standards and conditions."

The history of public housing in the United States largely begins in the 1930s during the Great Depression with the New Deal programs. Housing insecurity existed before, but the Depression provided the political impetus for the federal government to respond to an issue that had become a crisis. One of the first actions taken to address the nation’s growing housing crisis was the passage of the National Housing Act, which created the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) "to encourage improvements in housing standards and conditions."

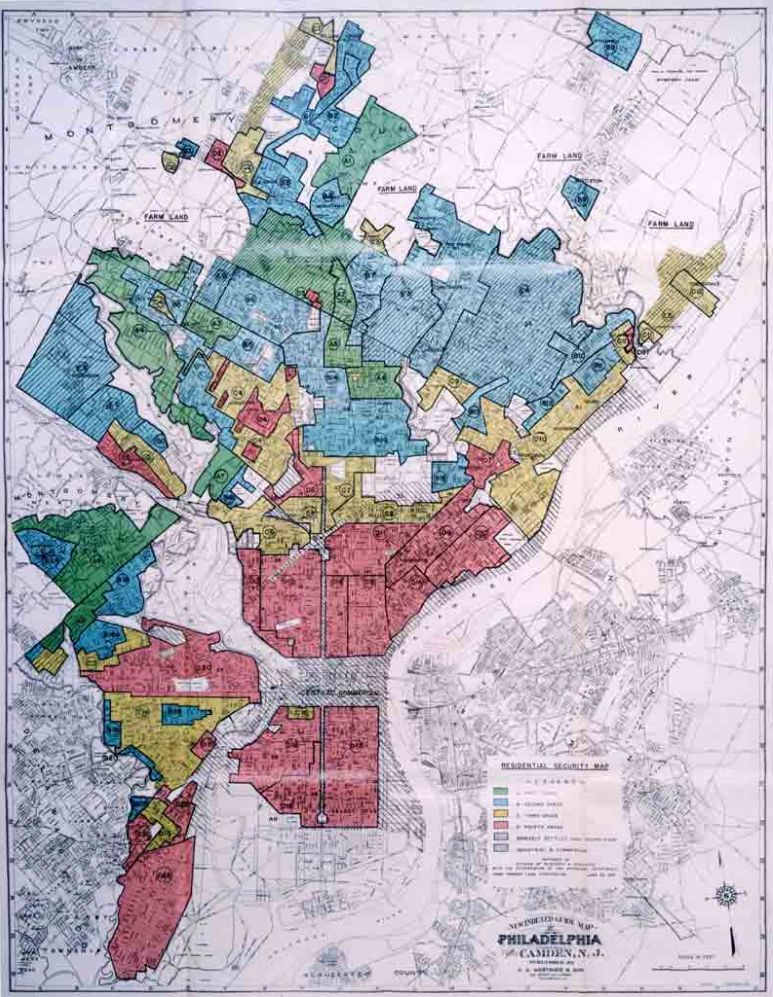

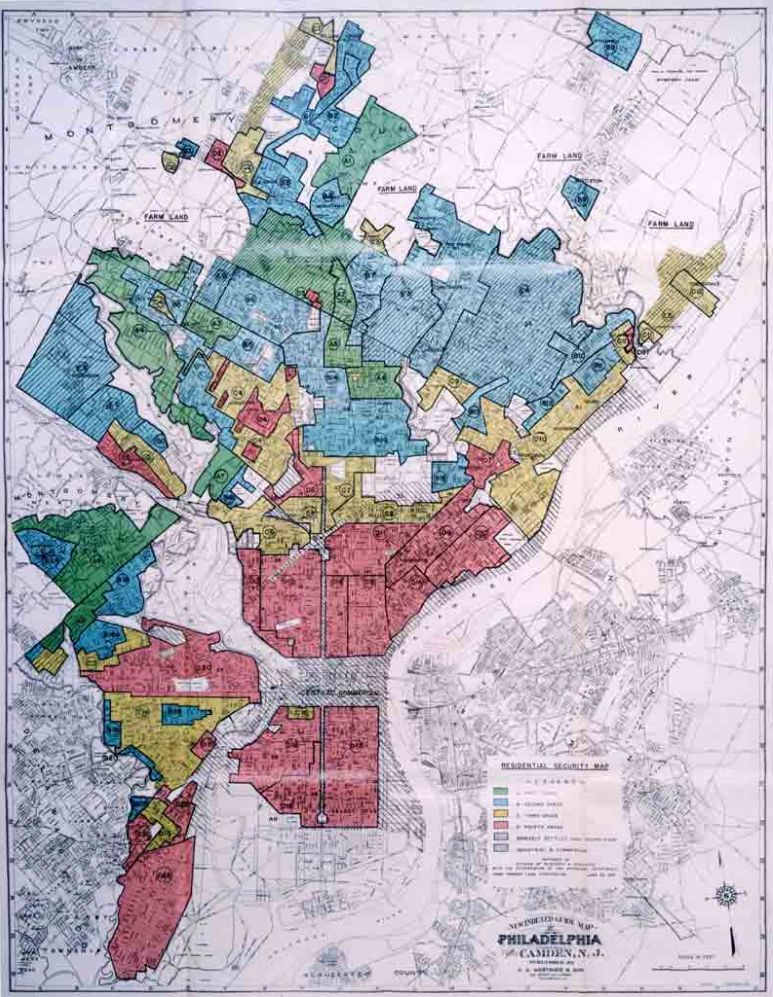

A 1939 report estimated that the FHA helps 12 million people improve their housing conditions, but that benefit was out of reach for millions more Americans. In his 2017 book, The Color of Law, author Richard Rothstein called the FHA a "state-sponsored system of discrimination" that was, "primarily designed to provide housing to white, middle-class, lower-middle-class families." The FHA refused to insure mortgages in African American neighborhoods, and required homes built by FHA loans to be sold only to white families, a policy known as redlining. Today, American cities continue to struggle with the inter-generational impact of redlining, segregated neighborhoods, and discriminatory lending practices.

1937 - United States Housing Act of 1937

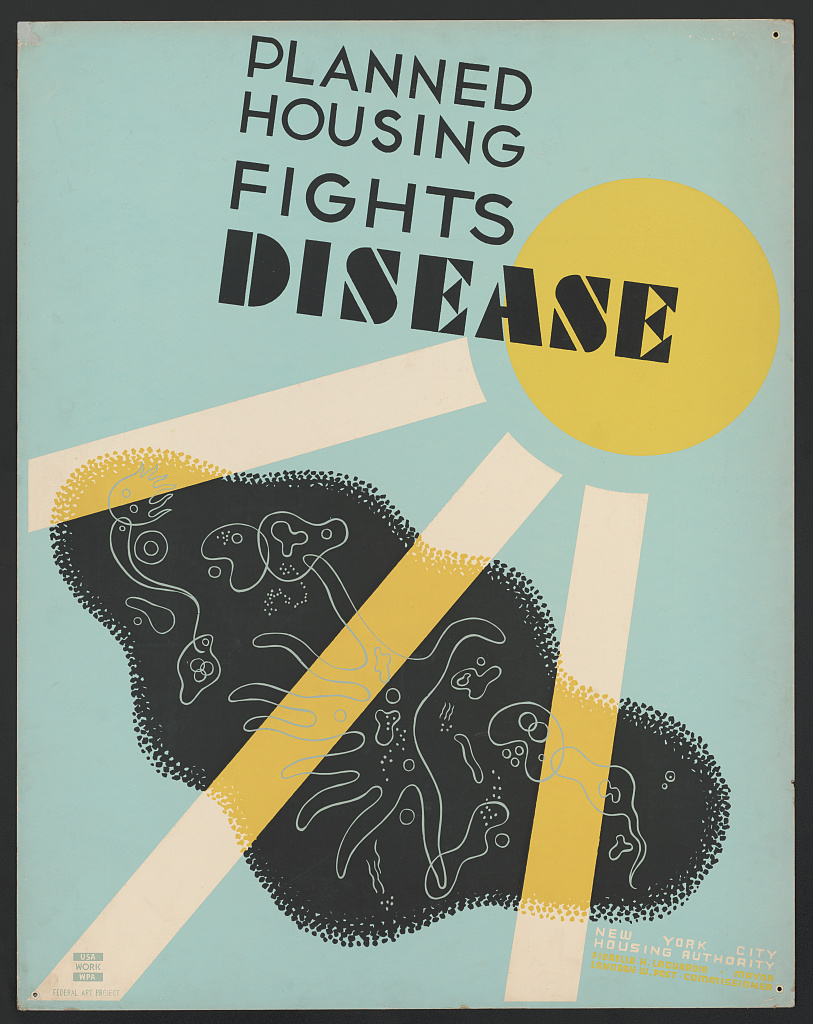

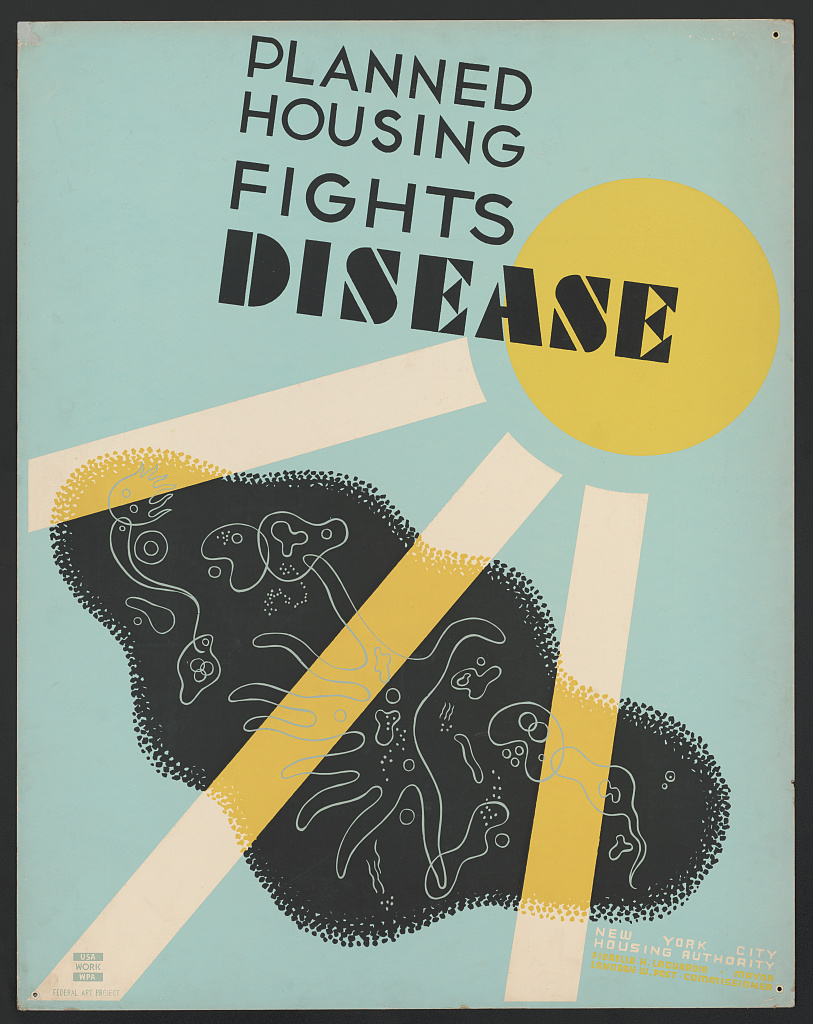

The United States Housing Act of 1937 established the nation’s public housing system and stated: “It is hereby declared to be the policy of the United States to promote the general welfare of the Nation.” The most significant implication of the law was that it provided federal subsidies to local housing authorities around the country, “for the elimination of unsafe and unsanitary housing conditions, for the eradication of slums, for the provision of decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings for families of low income.” This model shifted the federal government away from construction projects and toward loans supporting local housing authorities and state governments. Public housing policy and administration have since changed, but the Housing Act of 1937 created the model we have today: federal dollars funding local housing authorities.

The United States Housing Act of 1937 established the nation’s public housing system and stated: “It is hereby declared to be the policy of the United States to promote the general welfare of the Nation.” The most significant implication of the law was that it provided federal subsidies to local housing authorities around the country, “for the elimination of unsafe and unsanitary housing conditions, for the eradication of slums, for the provision of decent, safe, and sanitary dwellings for families of low income.” This model shifted the federal government away from construction projects and toward loans supporting local housing authorities and state governments. Public housing policy and administration have since changed, but the Housing Act of 1937 created the model we have today: federal dollars funding local housing authorities.

The Housing Act of 1937 was largely drafted by Catherine Bauer Wurster, a public housing and urban planning advocate, who became a Director at the newly formed United States Housing Authority. Alexander von Hoffman, Senior Fellow at the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, wrote that the Roosevelt administration was not supportive of public housing. He reported in 2012 that, “perhaps the greatest lesson of public housing is that during a crisis determined activists can, with skill and luck, impose an unorthodox policy on a government that under ordinary circumstances would reject it.”

1944 - G.I. Bill

On June 22, 1944, President Roosevelt signed into law the Servicemen's Readjustment Act, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, which created programs to help veterans of the Second World War. Those programs included low-cost mortgages and low-interest loans. Between 1944 and 1950, the Veterans Administration guaranteed over 2 million home loans, but these benefits and more were denied to black veterans. The G.I. Bill was written to give enormous power to local officials, which in the words of Historian Ira Katznelson: “the law was deliberately designed to accommodate Jim Crow.” This discrimination and the denial of benefits to which black veterans were entitled by law happened in both the North and South. Journalist and author Edward Humes reported in 2006 that officials, “didn’t merely discourage black veterans. They just said no. No to home loans. No to job placement, except for the most menial positions. And no to college, except for historically black colleges, maintaining the sham of ‘separate but equal’...” It is another part of America’s complicated history. The G.I. Bill made home improvement and ownership possible for millions of veterans, but did so through an unjust system of institutional racism - demonstrating that merely investing money in housing alone is ineffective without also addressing underlying issues of racism and other social determinants of health.

On June 22, 1944, President Roosevelt signed into law the Servicemen's Readjustment Act, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, which created programs to help veterans of the Second World War. Those programs included low-cost mortgages and low-interest loans. Between 1944 and 1950, the Veterans Administration guaranteed over 2 million home loans, but these benefits and more were denied to black veterans. The G.I. Bill was written to give enormous power to local officials, which in the words of Historian Ira Katznelson: “the law was deliberately designed to accommodate Jim Crow.” This discrimination and the denial of benefits to which black veterans were entitled by law happened in both the North and South. Journalist and author Edward Humes reported in 2006 that officials, “didn’t merely discourage black veterans. They just said no. No to home loans. No to job placement, except for the most menial positions. And no to college, except for historically black colleges, maintaining the sham of ‘separate but equal’...” It is another part of America’s complicated history. The G.I. Bill made home improvement and ownership possible for millions of veterans, but did so through an unjust system of institutional racism - demonstrating that merely investing money in housing alone is ineffective without also addressing underlying issues of racism and other social determinants of health.

1956 - Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956

In the minds of many, the ‘50s represent a time of American prosperity. A “post-war boom” saw the economy thrive throughout the decade, leading to increased homeownership and workforce productivity. It was in the midst of this boom that Congress passed an expansive piece of legislation that capitalized on America’s rapid growth through a major public works effort: the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956. While seemingly unrelated to public housing, this law had a major impact on communities across the country. The bill authorized the construction of the Interstate Highway System, a 41,000 mile stretch of road designed to connect the country’s network of cities. In theory, the bill would propel America’s upward swing. In practice, highways displaced traditionally low-income communities, cutting them off from important resources. They also encouraged the proliferation of suburbs - areas where predominantly white, middle-class residents migrated from city neighborhoods, further isolating and segregating disenfranchised communities. Many highways also bulldozed over “blighted” areas, a term steeped in discriminatory practice.

1968 - Fair Housing Act (Civil Rights Act of 1968)

On April 4, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed The Civil Rights Act of 1968 into law. It came one week after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. King’s legacy and influence cannot be overstated: his years of tireless advocacy, coupled with nonviolent activism and community organizing, helped inform the provisions of the Act aimed at dismantling the systemic, racist policies that governed nearly all aspects of American life. Major achievements included the titles that dealt with housing - known collectively as the Fair Housing Act (FHA). Through the FHA, citizens are protected from discrimation when buying or renting a home, with special provisions for those seeking federally-assisted housing. Common practices like blockbusting - where real estate agents encouraged white homeowners to sell their homes to avoid incoming black residents - were outlawed. The FHA marked a turning point for housing policy in the United States, and helped shape the foundation and trajectory of the newly-formed U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

On April 4, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed The Civil Rights Act of 1968 into law. It came one week after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. King’s legacy and influence cannot be overstated: his years of tireless advocacy, coupled with nonviolent activism and community organizing, helped inform the provisions of the Act aimed at dismantling the systemic, racist policies that governed nearly all aspects of American life. Major achievements included the titles that dealt with housing - known collectively as the Fair Housing Act (FHA). Through the FHA, citizens are protected from discrimation when buying or renting a home, with special provisions for those seeking federally-assisted housing. Common practices like blockbusting - where real estate agents encouraged white homeowners to sell their homes to avoid incoming black residents - were outlawed. The FHA marked a turning point for housing policy in the United States, and helped shape the foundation and trajectory of the newly-formed U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

1974 - Section 8 Amendment to the Housing Act

In 1974, Congress passed the Housing Choice Voucher Program, an amendment to Section 8 of the Housing Act of 1937. This created the Section 8 Program, which provides federal vouchers to low-income households to rent a home from a private landlord. Households pay about 30% of their income in rent, and the rest of the cost is covered by the federal voucher. Section 8 provides housing access to some of the people who need it the most and prevents homelessness, but it is a far from perfect program. In many areas of the country, families can wait years for approval for Section 8 housing assistance. Some local public housing agencies are no longer accepting applicants because their waiting lists are too long. Access is also limited because many landlords will not accept Section 8 vouchers. In 2017, NPR interviewed a Dallas mother who called hundreds of apartments in her search for a landlord who would accept Section 8 vouchers. Stories like this are not uncommon in areas with high demand for rental units. In many states, landlords are not required to accept vouchers, while in other states it is illegal to refuse to rent to a tenant because they have Section 8. Though this amendment was created to help the millions of individuals looking for suitable affordable housing, the program requires more changes to reduce and eliminate the discrimination Section 8 renters still face today.

1999 - Faircloth Amendment

The U.S. government has not funded the construction of any new public housing units in the last 20 years because of the Faircloth Amendment, which caps the number of public housing units allowable at their 1999 level. Since President Clinton signed the amendment, HUD can only replace existing units on a one-for-one basis, and is prohibited by law from building that would add more public housing units. The result is extra stress on a system that already cannot meet demand.

Public housing advocates have called this amendment “draconian,” and in 2017 Rep. Maxine Waters (D-MO) introduced a bill to repeal it. In March of this year, Anthony Scott, CEO of the Durham Housing Authority, testified on behalf of the Council of Large Public Housing Authorities to the U.S. House Committee on Appropriations. “This rule effectively and arbitrarily limits supply while making it difficult to increase the supply of affordable housing in local communities.” He described the Amendment as “unnecessarily” shackling local communities and preventing the development of new affordable housing. He concluded: “Simply put, the Faircloth Amendment needs to go.”

2012 - Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD)

HUD’s Rental Assistance Demonstration (RAD) program illustrates how public housing has shifted since its creation in the early 20th century. Public housing today is subsidized in part through private and public partnerships (in what’s referred to as mixed-financed housing), largely because the demand for affordable housing has outpaced the federal government’s ability to pay for it. A 2010 study showed that HUD had a backlog of $26 million in unmet capital needs (including much-needed repairs and maintenance). RAD is an effort to curb this trend. In part, RAD allows public housing authorities to convert a portion of their traditional, project-based housing to project-based voucher (PBV) or project-based rental assistance (PBRA) units, giving housing authorities the ability to borrow private funds to repair those units. Yet an increased reliance on private investment may limit HUD’s accountability for those units converted under the program. Private investors and developers are not held to the same standard of public scrutiny as a federal agency like HUD. Expanding the private sector’s involvement in public housing meets a financial need, but it remains to be seen whether it is beneficial to residents in the long term.

Emily Kane and Justin Gero contributed to this post.

LATEST BLOG POSTS

27 June 2024

Did you know that over half of US adults report that either they, or a family member, have experienced a...

14 April 2023

This is the fourth episode of our new Vaccine Confidence series on At the Core of Care. Over the course...

STAY CONNECTED TO NURSE-LED CARE

The history of public housing in the United States largely begins in the 1930s during the Great Depression with the

The history of public housing in the United States largely begins in the 1930s during the Great Depression with the  The

The  On June 22, 1944, President Roosevelt signed into law the Servicemen's Readjustment Act, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, which created programs to help veterans of the Second World War. Those programs included low-cost mortgages and low-interest loans. Between 1944 and 1950, the

On June 22, 1944, President Roosevelt signed into law the Servicemen's Readjustment Act, commonly known as the G.I. Bill, which created programs to help veterans of the Second World War. Those programs included low-cost mortgages and low-interest loans. Between 1944 and 1950, the  On April 4, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed The Civil Rights Act of 1968 into law. It came one week after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. King’s

On April 4, 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed The Civil Rights Act of 1968 into law. It came one week after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. King’s